How to Complain Christianly

Welcome Images. No modification. License.

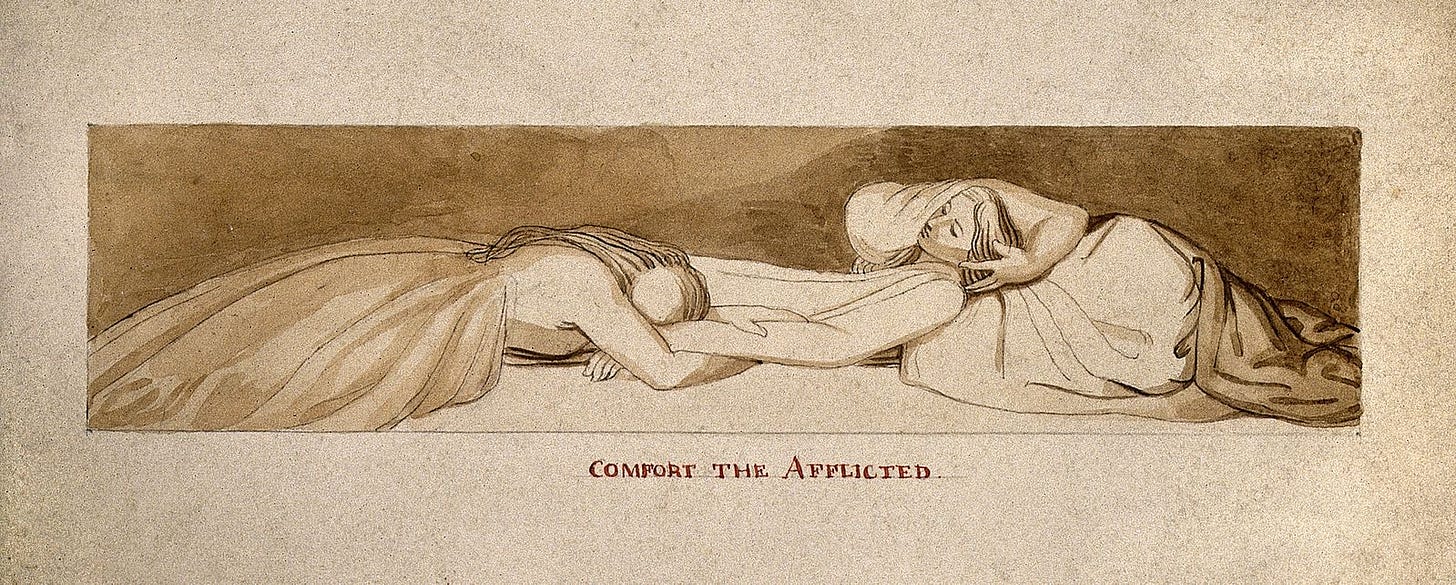

The Psalms also teach us to talk to God, to pray. They teach us how to complain to God and to praise God. How to accuse God, how to honour God. How to lament to him, how to thank him.

Many of us probably feel comfortable praising and honouring God, but it feels intuitively wrong to complain, accuse, or lament to him, and yet the Psalms often teach us to do just that.

We need to be very careful here, because simply telling God how you feel in all its ugliness can be a recipe for darkness, despair and God’s displeasure. The Psalms avoid these dark paths, and they instead lead us down a road of sorrow, reconciliation, and praise. They supply divine words to our distasteful experience. By speaking the words of the Psalms to God, we are really using words supplied by the Holy Spirit to work through our relationship with our Father.

God knows our weaknesses, and he gives us the very words we can speak to him in our weakness. As a result, when we see the psalmist weep, we weep. When we observe the psalmist lament, we lament. But when that same psalmist turns to confess the grace of God, we confess the grace of God. We turn our sorrow into praise, not by hiding the ugliness of sin and sorrow but by shining the light of God’s glory onto all of our messiness.

As a pastor, Saint Augustine recognized how God’s Spirit in the psalms supplies divine words for hurting people. He compares Romans 12:15 (“rejoice with those who rejoice; weep with those who weep) with Psalm 93, showing that the psalms rejoice and weep with us as it were as we struggle through life: “You first weep with him so that after he may rejoice with you; you share his sorrow in order to refresh him. So too the psalm, and indeed the Spirit of God, though knowing everything, ask questions with you, as though putting your own thoughts into words” (Augustine, “Exposition of Psalm 93,” 385–6 (§9). God’s Spirit and his word come alongside you in your sorrow when you read the psalms.

Reflect on Psalm 22, which begins with the famous phrase that Jesus quotes on the cross: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me” (Matt 27:46; Mark 15:34). David and presumably Jesus experienced a kind of darkness of the soul, which prompts the complaint. The twenty-second psalm continues: “Why are you so far from saving me, from the words of my groaning? O my God, I cry by day, but you do not answer, and by night, but I find no rest.”

I wonder if we could relate to this?

David doesn’t let his experience of darkness lead him deeper into it. He genuinely tells God how he feels, but in his complaint there is a confession. God should be close. God should save him. Psalm 22:19 reads, “But you, O LORD, do not be far off! O you my help, come quickly to my aid!”

David complains to God, and then redirects his complaint to confession. Finally, in Psalm 22:22–31, David turns to praise: “I will tell of your name to my brothers; in the midst of the congregation I will praise you” (v. 22); cf. Heb 2:12).

By reading Psalm 22 or psalms like it, you use divine words to mouth your complaint to God. But divine Scripture never allows you to wallow in complaint, it leads you to confession, and from confession to praise.

Praise heals broken souls.